The big picture: using wildflower strips for pest control

Perhaps it’s just the time of year, or perhaps it’s the increasing popularity of plant-based diets, but the Twittersphere is once again ablaze with claims that our food is far less nutritious than it used to be.

Is it true? Do we really have to eat twice as much broccoli? Have we killed the soil? And are we all going to die of scurvy?

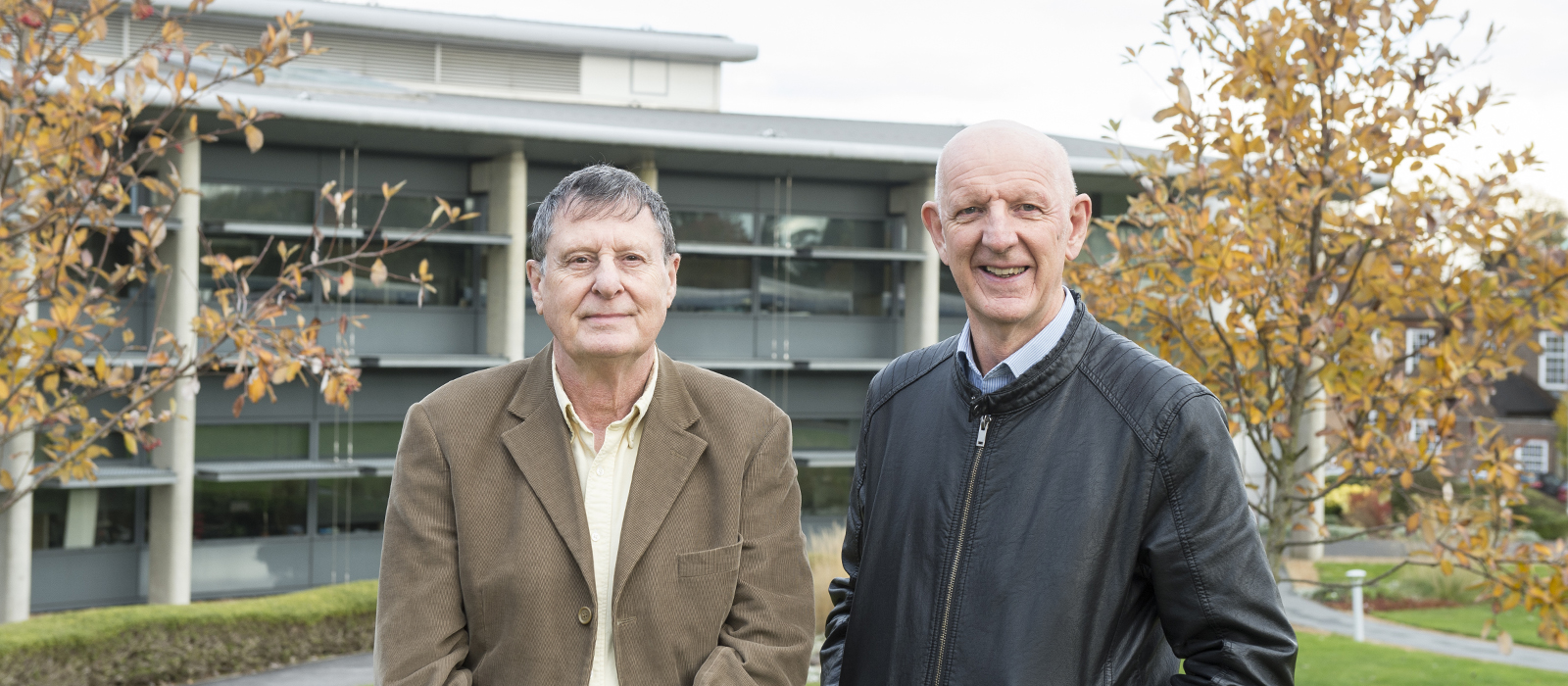

'Fact or Fake News' asked nutrient experts Professors Steve McGrath and Peter Shewry to set the record straight...

What’s the evidence?

PS: We need to be wary of comparisons of the compositions of old and recent types of crops - including wheat - because mineral content is strongly affected by the environment, especially soil conditions and the place where they are grown. It is therefore important to compare samples grown in controlled and replicated field trials and analysed using the same methods. There are very few studies in which this has been done.

SM: Really, the best evidence is our work on wheat from the Broadbalk experiment, which spans 175 years. No really good, controlled experimental studies on other staple crops or vegetables exist.

What do we know about wheat then?

SM: Wheat is an important source of minerals such as iron, zinc, copper and magnesium in the UK diet. If you look at the data, their concentrations remained stable between 1845 and the mid-1960s, but since then have decreased significantly - which coincided with the introduction of semi-dwarf, high-yielding wheat cultivars. The overall decrease in mineral content of between 20 and 30% is considerable.

So, we haven’t depleted the soil of nutrients?

SM: No. The concentrations of these nutrients in soil have either increased or remained stable over the last 160 years. And that’s not just total amounts, but also the amounts plants can take up via their roots. Looking at the Broadbalk study, you see similar trends of declining wheat nutrients in different treatments, whether they’ve received no fertilizers, inorganic fertilizers or organic manure. We can say definitively soil nutrient levels are not the cause.

What about soil microbes – is it something to do with changes in those?

SM: It seems not, as the crop composition in treatments with high nutrient additions has declined in the same way as that in the no fertiliser treatments.

If not the soil, what about climate change? Some people suggest rising CO2 is leading to faster growing, but less nutritious, crops.

SM: There are suggestions that climate change has increased yields, though the carbon dioxide fertilisation effect, and this could also dilute the nutrient concentrations (see ‘yield dilution’ below). However, looking at this effect it is small (region of 5%) and the change due to new varieties boosting yields is much greater. And of course, the climate effect comes with other impacts such as drought and high temperature that can decrease yield, so the proposed dilution may not occur.

So, what has caused this decline?

PS: One effect which may contribute to the decreased mineral contents of semi-dwarf wheats, and other high yielding modern crops is ‘yield dilution’. During the ‘green revolution’ of the 1960s, these newer wheat varieties were bred that had higher yields – the driver for this was to combat hunger across the rapidly expanding populations in the developing world. These varieties produce bigger and more grains, but that means an increased amount of starch - which dilutes other grain components including minerals. We have shown that semi-dwarf wheats also contain less minerals even when grown under the same conditions side by side with the old varieties. This demonstrates that is clearly a genetic effect and not due to environmental factors.

However, we need to know more about the impact of these decreases on human health, because iron in wheat has low bioavailability – a measure of the amount we can take up – in humans.

So why not use these old varieties?

PS: Farmers grow wheat for profitability, which is essentially yield and processing quality. These old varieties produce about a third of the grain that the newer, shorter varieties do.

SM: This was publicised by DeFries and colleagues. (Science 2015; 349, 238-240) who said what we need is a system where farmers should be paid for nutrient yield rather than just mass.

Does it matter?

SM: Less so in most developed countries as we tend to eat large portion sizes and varied diets but in many developing countries such as in Africa soils are often severely lacking in vital micronutrients such as zinc and selenium. When more modest diets are predominantly made up of one staple cereal crop such as wheat, rice, maize and sorghum- as is the case for many millions of people – then these micronutrient deficiencies or ‘hidden hunger’ become a real problem.

What’s the solution?

PS: There is sufficient genetic variation in micronutrient concentrations of major crops and their wild relatives, which can be explored in breeding strategies to combine the high nutrient density with the high-yielding traits. It just takes times to achieve it, particularly when using conventional breeding techniques.

SM: The solutions to micronutrient malnutrition include supplementation, diversification of diet, and biofortification of crops either by using fertiliser, or improved breeding. However, the low concentration and lack of bioavailability of nutrients in some soils is so severe that even micronutrient-improved varieties sometimes do not reach the targets for supplying dietary requirements. It’s a major problem for people who depend mainly on staple cereals grown on poor soils.

Fact or Fake News Conclusion: The Green Revolution unintentionally contributed to decreased mineral density in wheat grain. The impact on health is minimal in developed countries, but a major issue in Africa.

Further reading:

https://repository.rothamsted.ac.uk/item/8v257/is-modern-wheat-bad-for-health